How to Teach English Pronunciation Effectively

...and how to spot red flags in ineffective pronunciation courses.

In a 2011 Canadian study1, only 20% of qualified English as a Second Language (ESL) teachers reported ever taking a class on how to teach pronunciation.

In the same study, the researchers looked at university programs to see how many courses were offered specifically about teaching pronunciation. In all of Canada, they found six courses.

The trend is similar in the U.S: teachers generally aren’t taught how to teach pronunciation, and so they either avoid teaching it altogether, or they rely on their own intuition on how to best teach it.

And I’m no exception.

A couple years ago, I wanted to make a pronunciation course. “I’ve taken years of phonetics and phonology in university; it’ll be easy,” I thought. So, I started to design the course based on my intuition. But then I thought, “Wait, my phonetics and phonology classes never covered how to teach ESL pronunciation; let me buy a book about applied linguistics to double check my intuition.”

I bought Derwing and Munro’s book Pronunciation Fundamentals, and if I can summarize what I learned in one sentence it would be: I should not trust my intuition when it comes to teaching pronunciation.

Reading the book, I was shocked to find out that so much of what I’d seen online about how to teach pronunciation effectively goes directly against what research says.

This week, I’m going to outline key lessons from the book. I’m writing with teachers as my audience since the full newsletter is for paid subscribers and right now they’re all teachers. By the end, teachers will have links to quality free resources, and they’ll know what to focus on when they teach pronunciation. If you’re a student, you can use this newsletter to help you find a qualified pronunciation teacher or to start learning on your own.

Recap From Last Week: What Causes Pronunciation Differences?

As humans, we all have the same articulators to make sounds: lips, tongue, jaw, glottis…but not all languages in the world have the same sounds. Some languages only have two sounds, other languages, like American English, have over 40 sounds.

When you learn your first language, you learn the sounds both physically—you learn when to round your lips for each vowel—and mentally—you learn the phonological rules for each sound.

When you learn a second language, you need to train your articulators to make new sounds. And it could be really tricky because your first language may influence how you pronounce sounds in your second language. If you’re learning English as a Spanish speaker, for example, you might encounter a word like ‘cat’ and substitute the English /æ/ which Spanish doesn’t have with the sound /a/ which Spanish does have.

On top of physically learning new sounds, you also need to learn new phonological rules. Again, you might automatically apply the rules from your first language to your second language. If we stick to our Spanish speaker learning English, they might apply the Spanish rule ‘don’t start words with consonant clusters starting with /s/’ to English. They might encounter a word like ‘school’ and automatically add a vowel in front to not have a consonant cluster at the beginning of the word, pronouncing ‘school’ as /ɛskul/.

And then there are differences on the word and sentence level, like stress and rhythm.

But Wait, Do All Learners Have Transfer Errors From Their First Language?

It’s a good question.

Derwing and Munro investigated how true this idea of language transfer is when it comes to pronunciation. In particular, they tested this transfer error:

Russian doesn’t have aspirated stops at the beginning of words, but English does. So, Russian speakers are likely to pronounce words like ‘pop’ as ‘bop.’

The results of the study low-key shocked me:

Of the 24 Russian migrants tested, 14 of them automatically pronounced aspirated stops intelligibly either immediately or within the first few months of moving to Canada.

In other words, without any pronunciation work, 60% of these speakers didn’t transfer the rule from Russian.

Of the remaining 10, four naturally produced the sounds correctly after a few months (again, without training), and only 6 speakers still struggled with aspirated stops long term.

On one hand, it’s one study with a small group of participants. On the other hand, it’s suggesting that students’ errors can’t really be predicted, which is what we learned last week: second language pronunciation is highly variable. And that’s the reason why speakers of the same first language can have drastically different accents in English.

So, when it comes to pronunciation training, individual, personalized testing is a non-negotiable. In fact, I would consider pronunciation courses without an objective test before and after the course a red flag. Without a proper test, there’s no way to know if the student is really improving2.

How To Test Pronunciation Effectively

In this section, you’ll find ideas on how to assess students, links to resources, and ideas on how to prioritize different aspects of pronunciation.

Since it’s hard to predict which sounds students will have trouble perceiving, Derwing and Munro recommend testing the whole class on production first. Then, based on the individual students’ mistakes, you can test whether they can perceive the difference between the two sounds they’re confusing.

How To Test Production

For production, Derwing and Munro recommend some textbooks that have pre-made production tests and rubrics backed by research. I haven’t taken a look at them, but here are the ones they recommend:

Teaching Pronunciation (Celce-Murcia et al, 2010)

Clear Speech Teacher’s Resources and Assessment Book (Gilbert, 2012)

If you make your own tests, for production, two general good ideas are: 1.) Record the students so that both you and the students can look back on the progress 2.) Record the student both reading a script and speaking about a topic (we pronounce things differently when we read, so it’s great to have recordings of both scripted and extemporaneous speech.)

How To Test Perception

For segmentals3, Derwing and Munro recommend English Accent Coach. It was developed by a linguist. I’ve used it with students, and it helped them immensely, and it also helped me know which sounds the students could perceive. I really like it…and it’s free! It’s great for learning IPA, too.

You could also do in-class activities like:

Read out minimal pairs and students have to circle the vowel or consonant they hear

Read out three words and circle the “odd one out” in terms of primary stress (e.g. two words have primary stress on the first syllable, one has primary stress on the second syllable)

Have students transcribe a recording for general listening

Read out the same sentence with different intonation and test whether students understand what the change in intonation means

Not All Segmentals & Suprasegmentals Are Equal

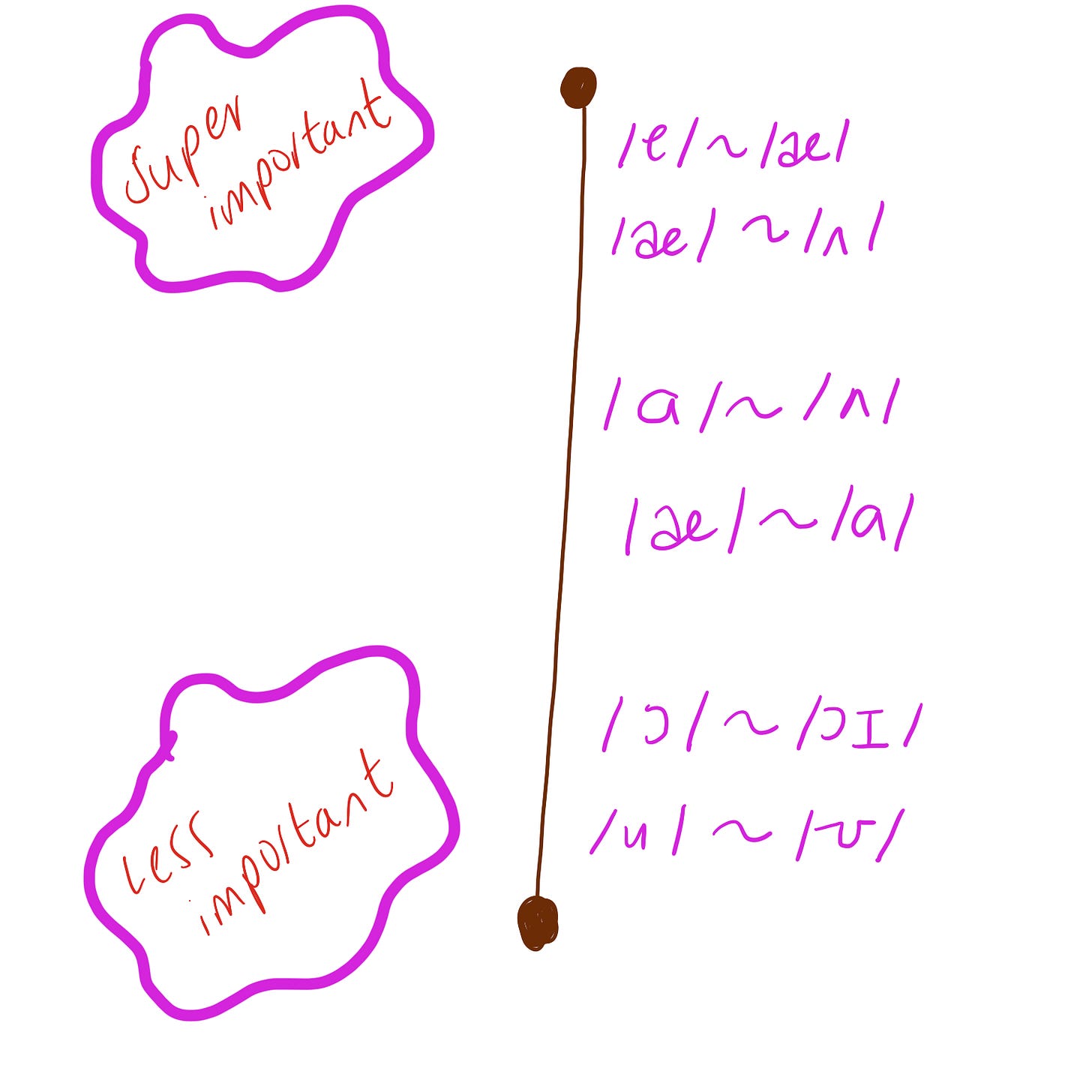

After you’ve tested your student, you might have an overwhelming amount of things to “correct.” A really promising theoretical idea for which sounds should be prioritized is called Functional Load.

Long story short, the researchers used statistics to contrast all English sounds that students tend to conflate to see which mistakes were worse than others. For example, if we look at voiced/unvoiced minimal pairs, the difference between /p/~/b/ is really important in English because there are many words that change meaning with just that sound. Compare the list of /p/~/b/ with the list of /θ/~/ð/:

pea~bee thigh~thy

pat~bat ?????

pet~bet

…

So, if a student is confusing /p/~/b/ and /θ/~/ð/, you should prioritize /p/~/b/. With this model, you can see that swapping /θ/~/ð/ 99.9% of the time won’t affect intelligibility. So you can consider ignoring that mistake.

To get the final list of Functional Load, they took into account:

The number of minimal pairs with those sounds

The frequency of the words in the minimal pairs (no one uses ‘thy’ so /θ/~/ð/ really doesn’t matter)

Whether the words in the minimal pairs had the same lexical class (you’re more likely to not understand a noun being replaced by another noun than a noun being replaced by a verb)

Finding out about Functional Load4, for me, was a weight off my shoulders because I could have the list of mistakes in front of me and then use the Functional Load chart to prioritize certain mistakes over others. There was no guess work or intuition on my side.

Teaching High-Frequency Segmentals

Once you know which sounds to prioritize, you can have students practice producing the sounds with the website Sounds of Speech. It’s an amazing resource because it shows the anatomy of how the sound is made and then has a video of the sound being produced in different word positions.

Suprasegmentals

Unfortunately, there hasn’t been too much research on which suprasegmental features should be prioritized. What we do know is that word-level stress is extremely important for intelligibility. Other than that, Derwing and Munro leave classic activities as examples of how to work on prosody:

Shadowing (you can also have students record themselves to assess how similar they sound to the original)

Dialogues (also great for practicing intonation)

Something I do find interesting is that Derwing and Munro never mention phonological rules like assimilation (the idea that the /t/ in ‘night cap’ is often blended into the /k/ sound as /naɪ kæp/). I see these types of rules all over social media as short and quick ways to learn pronunciation. If I had to guess why Derwing and Munro don’t mention them, it’s because 1.) these rules don’t affect intelligibility (only accent) 2.) these rules can absolutely make the student less intelligible if the student gets confused or messes up the rule (as in they only apply it sometimes).

Step-By-Step Summary

First, you want to record students both reading a script and speaking extemporaneously.

Then, you want to judge the recordings overall in terms in intelligibility and comprehensibility (based on your judgment as a teacher).

Next, you want to pinpoint areas of improvement (especially sounds and word-stress mistakes).

After, you want to test the student’s perception of sounds they conflated.

Finally, you want to use Functional Load to prioritize certain sounds. And you can add to your list suprasegmentals that you think made the student less intelligible or comprehensible.

In sum: teaching pronunciation effectively is HARD and time consuming. But imagine how much time you save by not having to cover each and every aspect of pronunciation. Through assessing, you can just work on the parts that matter. Let me know any thoughts or questions you have by replying to this email or commenting below.

Works Cited

Derwing, T. M., & Munro, M. J. (2015). Pronunciation fundamentals: Evidence-based perspectives for L2 teaching and research (Vol. 42). John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Foote et al. 2011

These courses often have hundreds of testimonials about improvement, but testimonials are weak; students are bad judges of their own pronunciation.

In the testimonials, students may write that they feel more confident after the course, (and I do love pronunciation courses that focus on mindset and confidence), but if the students are paying for pronunciation courses, they need to leave having improved in an objective way to get their money’s worth.

Segmentals = vowels and consonants

Suprasegmentals = rhythm, stress, intonation

If the paper doesn’t open for you, email me. If it does open, see Table 2 on page 604.

I have loved this and the previous post, thank you so much. As someone with an allergy to academic articles, this is exactly what I need :) I created a Pronunciation Training course based around problem sounds/ important phonological features based on my years of teaching, and it's encouraging to see a lot of what I did featured in this article - albeit with room for improvement on my part!

Coming to your point about why the authors don't cover teaching assimilation etc in pronunciation - I do teach this to students but not so much for their pronunciation It's for their listening skills. My mantra is if you can produce a sound, you can hear a sound, and I think that's important for learners to realise that teaching pronunciation and listening is completely connected. Improve one, and the other will follow.

Obviously it depends on the needs of the learner and who they use English with, but if they are living in an English speaking country or working with L1 speakers of British English for example, I like to raise their awareness of things like assimilation and showing them ways they can begin to bring it into their speaking (always emphasising that it's not for their communication but so they can better understand others).

Thanks for another amazing article. Very interesting and will certainly affect the way I approach teaching pronunciation. It would definitely be worth checking out the work of Jennifer Jenkins and the Lingua Franca Core.

She carried out a study that looked at the impact of segmental and suprasegmental errors on intelligibility and came up with some key findings on what areas of pronunciation should be focussed on.